Writing by Hildegard Westerkamp

Are you using a portable device? Please switch to landscape mode!

Sustainable Soundwalking - Passing on and relaying acoustic ecology's core practice

By Hildegard Westerkamp

Published in

the Proceedings of The Global Composition

2018, Conference on

Sound, Ecology, and Media Culture

Media Campus Dieburg, Hochschule Darmstadt, Germany, October 4-7, 2018

Those

of you who were present then, on August 13, 1993, will never forget when, a

short moment after the organization had officially been sanctioned, there was a

knocking sound on the window of the hall where we had gathered. One of the

frequent visitors to the grounds of the Banff Centre, an elk, was standing

outside. His antlers had done the knocking! We were already in a celebratory

mood, happy that we had brought together a community of like-minded sound

professionals by forming the WFAE. The timing of this unusual sonic event added

a touch of magic to the occasion and unleashed a wave of heart-warmed laughter.

Let’s celebrate this anniversary in a way that allows us to notice how our

listening and voicing can build bridges and deepen the connections between the

many diverse disciplines, approaches and interests among us.

It is the afternoon of August 28, 2018 on

Cortes Island, a small paradise, a day’s journey and three ferry rides away

from Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. I am leaning against a big log that

floated here probably many years ago after it came loose from a log boom,

transporting hundreds of logged trees to saw mills along the coast. I hear a

few crickets among other such logs and rocks behind me, seagulls and oyster

catchers in front of me and occasionally even a loon calling from way out on

the water. A group of women have gathered here for the workshop The Story from Hear, women who are interested in storytelling, listening and sound. Quite

a few of them came with years of professional experience, working in various

media contexts, where they learnt the tools of the trade. But here they are

eager to push through the learnt professional boundaries to tell stories in

creative ways, without the restrictions set by official media formats.

I

am hearing a helicopter pulsing in and out of the quiet among the surrounding

islands, wondering whether this sound is related to the many forest fires in

our province. After a few clearer days, I notice that smoke is moving in again.

A distant boat motor mingles with the throb and then disappears. Now I hear the

actual motor of the helicopter, as it comes closer, but nothing is straight

forward about this sound. Motor and throb are processed in varying ways by the

water and land formations, bouncing and reflecting here and there. Every detail

is audible, allowing me to descend with my ears, my whole being, into this

sound mix, that unfolds in front of me, mapping the sounds onto this landscape.

Six Canada geese just passed right in front of me, flying at eye level through

my ocean view frame, not even a metre above the sand, disrupting my helicopter

sound map with their calls in flight.

The

world needs to slow down--- is my thought at this moment. There is a sense of

refreshment in such moments of listening, as if taking a deep breath. For once

my time and space perception is in synch with the time and space that the

sounds occupy. My mind is not racing ahead to comment and interpret, to plan or

to meet a deadline.

Twenty years before

the founding of the WFAE in the summer of 1973, my colleague Barry Truax and I

had just been hired to work with the World Soundscape Project (WSP), which was

then in full swing with our colleagues Howard Broomfield, Bruce Davis and Peter

Huse, under the direction of R. Murray Schafer. They were in the middle of

producing and releasing The Vancouver

Soundscape, a document consisting of 2 LPs and an extensive booklet. A

4-page list of research projects had been created and each one of us put our

names to those that interested us the most. Each of these topics was defined

and outlined in further detail, a type of guideline that showed the vast

potential for further study of the sonic environment. For example, to name just

a few, there were research suggestions such as: the creation of a Glossary of Sound in Literature,

collecting evocative quotations concerning sound from all over the world’s

literature; an

Archive of Lost and Disappearing Sounds;

an investigation of Community Soundmarks;

a design project for the construction of an Acoustic

Park; an investigation of music in restaurants entitled A Listener’s Guide to Good Eating; a

study of The Sound Environment of Schools;

Soundscape Notations, experimenting

with notating soundscapes graphically; a study of the Semantics of Sound; or a

series of Sound Association or Sound Preference test. Most of these

were ongoing projects for study, results of which ended up in Schafer’s seminal

book The Tuning of the World. Many of

them continue to be relevant topics for study and could be picked up by interested

scholars of today.

The

Internet and social media would have served us well then, especially for

projects involving international participants and other cultures - such as A World Survey of Community Noise Bylaws;

an investigation of Onomatopoeia in

Different Cultures; or an international Car Horn Count, and more. We used to gather such information by

postal mail. Even fax did not exist, let alone email. Just recently two posts

on the Acoustic Ecology list, highlighted to me once again how easy it can be

to gather similar such information nowadays. One was researching warning signals such as pedestrian traffic light sounds

designed for the visually impaired. He posted a request for short

recordings of these sounds, a photo and

information about the location. “I’m interested in surveying possible cultural

pre-comprehensions, cultural biases, underlying the acts of both listening and

designing sounds.” The other one

was studying back-up truck alarms in the

city of Genoa, Italy, but was also interested in sources and information from

other countries, such as the US and Canada. “I am looking for laws,

requirements, regulations, enforcement, and exceptions; alternatives such as

white noise technology; studies/publications on the environmental impact on

human and non-human animals. Has this strand of noise pollution been

specifically researched, yet?”

The

Internet has enabled all sorts of new forms of expressions and sound activities

that could not have existed in the ‘70s. I’ll just mention one in particular

here, mostly because it has engendered various contradictory responses in me: the

so-called Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR)[2].

Videos showing many different approaches to ASMR can be found on YouTube and are

supposed to relax listeners/viewers, reduce stress and improve sleep. This

response – a subjective experience of "low-grade euphoria"

characterized by "a combination of positive feelings and a distinct

static-like tingling sensation on the skin"[3]

– is triggered mostly by various high frequency auditory stimuli. Sounds like

crinkling plastic or candy wrapper, fingers brushing through long hair, a soft

brush stroking the microphone itself that records all this, the quiet rattling

of beads, soft strokes on skin or along the spikes of a comb are presented in a

whispering voice and usually by a smiling young woman. “The phrase brain orgasm has also been used, and ASMR videos have been

described as whisper porn, although

these terms are misleading. Despite the intimate nature of ASMR videos, the

sensation itself is distinctly non-sexual and is pleasurable in the same way as

a blissful meditative state might be.”[4]

Bizarre

as this seems, it is perhaps not surprising that millions of visitors

frequent these sites, as if there is a social need for such listening

sensations. It also brings to mind Alfred Tomatis’ claim that listening to high

frequencies stimulates our brain. In my own soundwalks - it occurs to me - I also

and inadvertently have performed ASMR when I have picked up materials such as

dry leaves, seed pods, rocks and sticks during a walk, and made quiet small

sounds with them close to each participant’s ears. Quiet environments inspire

such actions, but also years of recording, experiencing similar listening sensations

through headphones, when leading the microphone close-up to a sound, such as a

water trickle in the forest, plucking the spikes of a cactus in the desert, or playing

on icicles in winter-white silence. There is indeed something delicious,

intimate and stimulating in hearing such close up sounds.

The tide is moving in quietly and calmly in

these inter island waters that are very still today. No big waves, no wind. I

am beginning to hear delicious little gurgles as the water creeps up closer,

finding its way through rocks and pebbles. The smoke is getting thicker, I cannot

see the coastal mountains anymore. The more distant islands have disappeared in

the fast but silently encroaching smoke. This is distressing. The one day of

rain has not stopped the fires sufficiently.

Our

time here in the context of The Story

from Hear puts a profound and different

emphasis on the world of hectic and density from which we all came. We are

working hard here during our five days of intense listening, recording, and

sound production, developing a sense of this place through sounds, voices and

stories. This place is quiet, but

alive with sound. At times however, it can be so quiet that the microphone-ears

are hungry for sounds. Rocks, wood or

any material become potential soundmaking instruments. The results are clear

recordings, with individual discreet sounds voicing their place in this

environment. We do not need a sound proof studio to get clear recordings. Our

ears and microphones are not bombarded by constant sound input, not occupied

with continuous work stress, even though we are working very hard. We can

safely open up to this place. In turn our perception, our physical and psychic

being opens up to a world we can trust, not to be attacked by loud noises,

hostilities, deadlines. From such a feeling of safety we learn to listen differently.

This situation is an

extraordinary luxury and the question becomes, how can we build something like

this into our daily lives. Taking the time to listen goes against today’s 24/7 status quo of hectic and

stress, of racing towards riches and success, of never having time and always

being importantly busy. In this larger context soundwalks become a conscious

practice in learning to change our pace in a society dangerously speeding out

of control.[5]

It means that we conduct soundwalks in

all types of environments - including those that are filled with a 24/7

atmospheres - in order to understand what the characteristics of soundscapes are

in a stressful work environment, in a hectic lifestyle, or how certain

soundscapes contribute to increased stress and hectic. In those types of

soundwalks in particular, it is crucial that we plan them with a sense of

safety in mind, with opportunities for participants to search out places of

sonic repose, or create sonic breathing space, whatever that may be for any

given situation.

I am

suggesting, that our listening be an ongoing practice, so that we build up

understanding of and resilience towards all kinds of sound environments –

a listening practice so present and attentive that it asserts change inside us

over time, and as a result eventually in the soundscape, in our communication

with others, in society at large. It is a state of ongoing attention.[6] The intent really is to set a framework that

allows soundwalk participants to move deeply into their experience of listening,

no matter where the walk takes place. By extension it begs the question, how we

might develop soundscapes, social environments, living spaces, places of

learning or work, for safe and open listening, with all living beings in mind.

Starting in our own lives is a good beginning, establishing a more grounded

footing from where we can branch out.

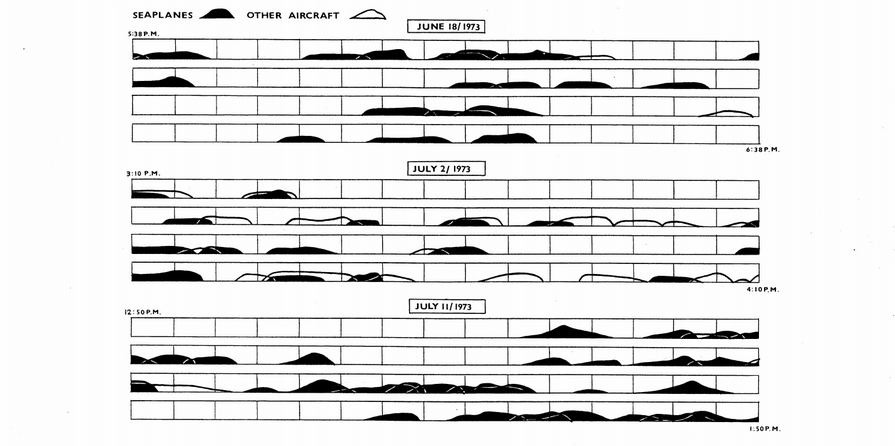

I

had just started to work for the WSP when I was asked to go to Ambleside Park

in West Vancouver, sit on the beach and count airplanes for one hour on three

different days. My task was to count seaplanes in particular, plus any other

aircraft, and mark them down on a prepared time graph, on which I was to draw

my subjective impressions of the planes’ loudness levels.

Figure 1: The diagram shows the

amount of time the sky over Stanley Park is filled with aircraft noise, from

the moment each aircraft appears on the acoustic horizon until it disappears.

In 1973 this amounted to 27 minutes per hour.[7]

Ambleside Park is located across from Stanley Park in Vancouver and

near Lion’s Gate Bridge. The seaplanes that take off from Vancouver’s harbour,

fly over the bridge, and those that descend for landing in the harbour, fly

over Stanley Park, all of them at very low altitude in their ascent or descent.

The

story has it that these seaplanes were the culprit: they had disturbed Schafer

while composing, when he lived in West Vancouver near Ambleside Park in the

late 60s. Eventually that experience triggered this small study with

interesting results. “In 1969 we conducted a social survey on seaplane noise

among 32 residents on Sentinel Hill, next to Ambleside Park, where we made our

counts. We repeated this again in 1973 among 30 residents in the same area. The

most startling fact in this survey is the discrepancy between the number of

planes residents imagined they heard per day and the number that were actually

present: 1969 – compare 8 with 65; 1973 – compare 16 with 106.”[8]

This

summer by chance while mentoring two young women, we discovered that the three

dates on which these counts had been done, fell on the exact same weekdays as

45 years ago: Monday June 18, Monday July 2, (a holiday on the Canada Day long

weekend), and Wednesday July 11! This was enough impetus to repeat the count,

do it at the exact same times of day and replicate the findings on similarly

structured graphs.

Figure 2: The three airplane counts

done this summer (2018), executed by Elizabeth Ellis, who worked with me as a

student in acoustic ecology, with emphasis on soundwalk training and other

forms of listening.

When comparing this summer’s counts to those of 1973, we found the

following results:

Generally speaking

one can observe that more minutes per hour were occupied by aircraft sounds in

2018, in comparison to 45 years ago. The busiest hour occurred on July 11, when

there were only 9 minutes without any

airplane sounds. More significantly, these pauses were filled by drones from

passing boats, traffic from Lion’s Gate Bridge and nearby building

construction. Elizabeth’s notes elaborate on that situation:

Between the aircrafts, boats, nearby construction, the traffic

behind me on Marine Drive and on the Lions Gate Bridge, there was a constant

loud hum. At times I thought I might have heard a plane but couldn’t see it,

and it was difficult to discern its sounds against the other drones –

likewise, I could see some distant planes but could not hear them distinctly.

So there were likely more planes in the airspace than what I had tracked on

paper.

She also observed that the passing boats masked the bridge traffic,

which in turn masked the approaching seaplanes. They only became audible when

they reached the same height as the bridge and appeared “as if out of nowhere”,

as she noted, from behind the traffic hum. The other aircrafts in this study

were mostly helicopters, one of them circling over downtown for at least 6

minutes. This is a marked difference from the 1973 study, where the other

aircrafts were mostly jet planes (and comparatively fewer in number). Some of

the ‘other aircraft’ noted on July 2, 1973, most likely were private small

aircraft, that is, recreational activity on a sunny Canada Day long weekend. I

don’t recall helicopters from those counts, most likely because the helicopter

pad located downtown by the harbour had not been built yet.

Although the time grids of the other two days this summer show a few more minutes without aircraft sound (15 ½ and 16 ½ minutes), the general sense is, that these sounds were as much part of the overall and constant drone as the road and boat traffic, as well as the nearby construction. Not so in 1973. In fact, I remember that I could trace the seaplane sounds from beginning to end, that is, they were not masked significantly by other transportation noises. It may be precisely this that made them stand out so much from the general ambience and as a result the planes would have been perceived as a real nuisance - not just by Schafer but as I recall, also by people working in offices near the harbour’s waterfront. Were we to conduct a similar social survey now with residents in the area as was done in 1973, my conjecture is that the seaplane sounds might be noticed even less than 45 years ago, precisely because they seem to blend more smoothly into today’s denser mix of transportation sounds. It could also be that seaplane motors have become quieter since then and therefore no longer stand out as much. Nowadays it may indeed be the helicopter sounds that would be noticed the most.

This

study was executed entirely through listening and could be understood as an ear

witness account of airplane behaviour in this part of Vancouver. Like a

soundwalk it revealed the character of this soundscape. But unlike a soundwalk

where participants are usually encouraged to open up to all possible sounds, the listener in this study was asked to focus

on one type of sound only. The result was that a very specific aspect of the

soundscape was highlighted while awareness of the sound environment as a whole

was maintained.

To engage seriously in the field of acoustic

ecology requires, as it does for all ecologists, to know, what Pauline Oliveros

calls the two “attention archetypes. These two modes are ....focal attention

and...global, or diffuse attention. These attention archetypes are

complementary processes. Both modes are necessary for survival and for the

success of our activities.” Applied to acoustic ecology it means to apply our

focused attention to specific acoustic concerns while staying connected to all knowledge about the acoustic

environment. It is like listening

itself: lending an attentive, focal ear to detail while at the same time

hearing, being aware of the soundscape as a whole.

No boat motors at this moment. One cricket

keeps sounding and the gently lapping water of the incoming tide sounds closer

now, like an intimate whisper near my ear. It is extraordinarily quiet. But

there is something unsettling about it. I hear no birds. It is as if the smoke

has silenced them. Suddenly the cricket sounds desolate. The air around us is

ever more thickened by the smoke that has crept in gradually and quietly. It is

a grey and static stillness, enlivened only by the lazily lapping wavelets and

an occasional breeze around my ears. Take a moment and compare this soundscape

to your own. Yes, do open up to it and listen to it in all its detail, as if it

was totally new to you. How does it affect you? Does it sound like a safe

environment? Do aspects of it unsettle you?

Acoustic Ecology is still

a relatively new field of study and is continually in the process of defining

itself. But one thing is certain: that its concern about the relationship

between soundscape and listener and how the nature of this relationship makes

out the character of any given soundscape, puts it squarely into the centre of

ecological thinking. Listening to the soundscape, in the context of this work,

is at least as important for deepening our understanding of the soundscape as

is research and study. In fact, it is perceived as the crucial and meaningful

link between all fields of study in sound and the need for action towards

soundscape improvements. In other words, listening is believed to be the very

focus that makes all study in sound environmentally and ecologically meaningful

and effective. Thus, a combination of rigorous aural awareness of our

environment and in-depth studies of all aspects of sound and the soundscape is

a way in which the acoustic ecologist can attempt to tackle the sound issues in

today’s world. [9]

Field

recordist and musician Peter Cusack tackles an urban soundscape ingeniously and

tells us about it in his beautiful

small book Berlin Sonic Places, A Brief

Guide:

City residents get to know particular sonic places very well.

Indeed, those at home or on regular travel routes become so familiar that they

virtually disappear from our awareness. This does not mean that they are

unimportant. On the contrary, their very familiarity means that they are

essential to personal city knowledge, key to our sense of place and vital to

our navigation through urban geography.

Berlin Sonic Places: a Brief Guide is an attempt to draw attention again.

Not only to the number and variety of sonic places in the city, but to their

intricacy, interest and continuing significance. They are the small beauties of

everyday sound and, sadly, too often ignored.[10]

Ever so often a

journalist is hit by the reality that noise is an ecological issue, can

dangerously affect our health and interferes not just in human communication

but also in that of the animal world. At that point we typically get an article

in the newspaper with titles like Sonic

Doom: how noise pollution can turn deadly, one that was published recently

in the Guardian Weekly.[11]

Alarm bells ring for a while, but nothing changes. There is little or no follow-up,

let alone real action towards reducing the noise problem. I have observed this

pattern ever since the 1970s. But at least the journalist’s ears have been

touched enough to move him into the action of writing.

Such

singular articles usually start with a personal account of the journalist’s

experiences with noise in their lives or even while trying to write the article

– just like I sprinkled this text with my impressions of the soundscape

in which I am doing the writing. It is a moment of listening, almost like in a

soundwalk, that grounds the writer in his or her sonic reality and enables a

type of sonic writing, a tone that hopes

to draw readers into listening to their own soundscapes and be touched by the

information in the article. Someone will always be touched.

Without knowing what enters our ears and without

understanding the environmental, social, cultural and personal implications of

this input, there can be no study of acoustic ecology. Daily practice of

listening develops in each one of us a conscious physical, emotional, and

mental relationship to the environment. And to understand this relationship is,

in itself, an essential tool for the study of the soundscape and provides

important motivation for engaging with today’s acoustic ecology issues—no

matter whether the context is our personal or our professional life. In

addition, listening creates the much-needed continuity in an otherwise

fragmented field of study or area of environmental concern.[12]

Max Dixon in London, speaking from the

perspective of town planning and urban design, emphasizes this for today’s

readers:

The soundscape approach recognises the complexity of human

responses. Its focus is on the meaning of sounds. Evaluation is largely through

perceptual effects. It recognises the limits of acoustic measurement. It adopts

a holistic approach. Perception is governed by the relationship between an

individual and specific environment, as currently experienced, as influenced by

memory, or by expectations or meaning.[13]

Although none of this is new to those of us who have worked in the

soundscape field since the 1970s, his rewording into a language appropriate for

today, for younger ears, is invaluable. What is new since then, is the fact that these words are coming from

someone whose professional focus is in urban planning and design. He also

reminds us, that

Guided listening walks, in which we bring the powers of ‘the

audience’ to bear, can be valuable engagement. Practitioners also need to develop

new ways of observing people’s actual behavior, rather than just asking them

what they think. …Public engagement should not mean a lowest common denominator

or what is already ‘popular’. We need to develop new modes of co-creation. We

need to respect local autonomy and a wide range of human needs differing across

time and space. We need to encourage creative specialists such as sound artists

to offer new possibilities with integrity.[14]

…Developing such innovation will require a range of skills, from acousticians

to planners, architects and other designers. But we also need visionary

impulses to inspire new thinking. In short, we need a new “Sonic Land Art”.[15]

Recently we have been warned by the US publication of

a ‘heat map’ which charts road and aviation noise, in which parts of the

country the din from traffic and airplane noise is the most unrelenting. “It

also reveals where sound is an environmental justice issue. Some of the loudest

urban neighborhoods are also the poorest.”[16]

And an earlier article from 2012 suggests:

Maybe it’s time to start looking at

townhouses and bus shelters with the same acoustic care engineers have long

given to concert halls and schools. In doing so, it’s possible we could make

the city sound not just quieter – but, in a very real way, more pleasant.[17]

Imagine if all

sound-related disciplines added soundscape listening, analysis and topics of

acoustic ecology to their course curriculum. Imagine if, for example, future

nurses, doctors, and medical staff were trained to conduct soundwalks through

hospital environments followed by critical sound analyses and connect the

results of such study to questions of convalescence and healing. Imagine if

architecture students were requested to analyse acoustic environments of

existing buildings with the same intensity as music students are asked to

analyse existing musical compositions; or if students of urban planning were

asked to analyse acoustic environments of existing parks or residential areas;

if sound design and soundscape analysis were as high a priority in film schools

as visual design and script writing; if environmental studies departments made

courses on sound ecology a high priority; if business courses emphasized

silence as a marketing tool for all machinery; if police education would teach

the complexities of law enforcement in noise issues; if clothes designer

courses would teach about the sound of fabric; if journalism courses would create

ear cleaning courses focusing on the sound of language, voice, sound and music

in media; if school teachers and principals were trained to create school

soundscapes conducive to learning?

Some

of this type of education, I am sure, already exists in many parts of the

world, probably in small pockets, where an individual or group are seriously

concerned with the quality of sound environments. It may exist formally as a

course in an educational institution; or less obviously as a subtle influence

on listeners in public spaces through conscious design; or informally in daily

life where an intensely listening person influences those that cross his or her

path. [18]

I am grateful for being around indigenous

sensibilities from the three young women in the workshop, who believe in

uncovering, recovering, their culture, stories, myths, languages, histories.

They are here to explore the aural dimensions of their own indigenous culture,

finding ways that connect to their aural roots and retelling their stories and

existences through the sound medium of radio and podcasting. Aware of the

damage that has been dealt them, their families and ancestors, they are putting

their energies into rebuilding, re-growing their cultural roots and their

confidence. And they are doing this courageously from the few remains that have

survived the destruction, having – really - to reinvent, because so much

knowledge has been lost, working with whatever tools are available to

them. I sense how much their

creations are driven by the love to their children and elders, by their

connection to the land and their deep respect of the natural world. Meanwhile

they are teaching us – the non-indigenous – something through their

grounded and quiet ways of listening – something that is almost too

ephemeral to grasp, let alone articulate. Will those of us who are not

indigenous, take the time to listen to indigenous voices? Will indigenous

people allow for our questions and inevitable mistakes that are bound to occur

along the way of reconciliation? Will we listen with them through their

silences – silences that often seem rather long to us, but in actual fact

are active pauses in time, places of a listening-to-the-heart, in search of

words that will truly voice the essences of their cultures?

Remember, we are in the inevitable tow

of ecological gravity, not economic haste. Ecosystems spiral slowly forward in

time-—evolving—and if they are to survive, economies will have to

eventually synchronize with the ecologic tempo.[19]

And I might add, …with

the indigenous tempo that has traditionally been in tune with the ecologic one.

Some have observed that, by setting up a situation where listening is the

central focus for learning, information gathering, mutual understanding and

reconciliation, a whole new dynamic emerges: respect for everything and

everybody that is heard and an equalization of differences and hierarchies. In

other words, it is not so much the pedagogical approach or an educational

method that deepens the understanding of ecological, social, and cultural

relationships, but the action of listening itself.

[1] The WFAE was founded

at the end of The First International

Conference on Acoustic Ecology, The Tuning of the World, at the Banff Centre

for the Arts, Banff, Alberta Canada, August 8-14, 1993.

[3] ibid.

[5]Quoted from: Hildegard

Westerkamp, The Disruptive Nature of

Listening, Keynote Address ISEA2015, Vancouver, B.C. Canada, August 18,

2015. http://www.hildegardwesterkamp...;title=the-disruptive-nature-of-l

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Vancouver Soundscape booklet, World Soundscape Project,

Document No. 5, Simon Fraser University, 1973, p. 49

[8] Ibid. p. 49

[9] Hildegard Westerkamp,

Editorial, Soundscape – The Journal

of Acoustic Ecology, Vol 1, No. 1, Spring 2000. P. 4

[10] Peter Cusack, Berlin Sonic Places, a Brief Guide,

DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program, 2017. P 8.

[11] Richard Godwin, Sonic Doom: how noise

pollution can turn deadly, Guardian Weekly, July

13-19, 2018, p. 34

[12] Hildegard Westerkamp,

Editorial, Soundscape – The Journal

of Acoustic Ecology, Vol 1, No 1, Spring 2000. p. 3

[13] Dixon, Max. “Towards a

new Sonic Land Art”, in Berlin Sonic

Places, a Brief Guide by Peter Cusack, DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program,

2017. P 9.

[14] ibid. pp. 8/9

[15] ibid. p. 11

[18] These last two

paragraphs are quoted from: Hildegard Westerkamp, Editorial, Soundscape – The Journal of Acoustic

Ecology, Vol 2, No. 2, December 2001. p. 3.

[19] Tom Jay, From an address to the Northwest Aquatic and Marine

Educators, in Port Townsend Washington, August 2, 2000.